STORIES / Okara’shòn:’a

Another mouth

As soon as those kids made it clear of the car, she put it in reverse and we got out of there. A few minutes later, she parked on the side of the road and she cried and cried. I just didn’t know what was happening.

Don't tell Brisebois

When I signed up for my courses, the woman from Sir George Williams College took out this ledger and said, “You’re one of the first to sign up from Indian Affairs. Here’s a voucher. Go get all of the books you need and give me the voucher when you’re done.” So, I did that. She must’ve sent the bill to Ottawa and they gave it to Brisebois.

Those are our orders

One night, we tried to get in after work and there were big crowds of like 200 people at all the checkpoints. We didn’t even try coming in, so we went back to Valleyfield and found a parking lot to stay in. Maybe two or three in the morning, we heard knocking on the window and we were surrounded by the SQ.

Always something

There was another time when it was a hot day, and our bus was taking us down St. Germain Road to the back of the monastery where we were supposed to be meeting government officials for another day of negotiations. When we arrived, the SQ was there waiting for us.

Ice water in our veins

Our big negotiation was that we wanted food and medicine let in passed the barricades, as well as international observers. When we talked to news reporters about these demands and concerns, they took it as us saying we just wanted all of the land back. They totally misconstrued everything.

Pivotal moment in Indigenous history

In 1990, the people thought we’d just get arrested; we didn’t expect to be shot at. We didn’t know that the SWAT team would be the ones to do the politician’s dirty work or that they would open fire upon us.

Restore the friendship

When they had the crisis in Kanesatà:ke back in 1990, a lot of people had bad feelings towards us. So, we had powwows to restore the friendship. We said, “Come and find out for yourself.” And they did find out. They never dealt with people so friendly.

Echoes of a proud nation

We decided we would choose the second weekend in July to commemorate what had happened that weekend in 1990. We also chose to host the powwow in the same area that the army had tried to invade in Kahnawà:ke, honouring the resilience of our community.

Fishing trip

My husband would go fishing all the time. I went with him once and told him, “Don’t ever ask me to go with you again.” Because it didn’t work out when we went, we got stuck.

Those guns won’t stop me

In 1990, we didn’t have any supplies in Kahnawà:ke because of the blockades. My husband Jimmy had a boat and my sister, Melissa, wanted to go shopping so Jimmy said, “Well okay Mel, get in my boat and I’ll take you.” She got on at Johnson’s Beach, and when they were halfway to the store, they had to land where the old movie theatre was in Dorval.

Could've died

When I was a kid, I remember seeing the older women, the grandmothers, swimming in the river. They were very modest and they wore handmade black dresses, even for swimming. I think they would jump into the river behind the church and float way out in the middle of the river. We could hear them laughing and laughing, floating down with their dresses that would make an air bubble around them.

The mighty St. Lawrence river

The St. Lawrence River played an important role in our daily lives, especially for families living by the riverside in the old village area of Kahnawake. On sunny nice days, community women would go down to the shore and wash laundry with large bar soap and scrub boards in hand and children in tow.

Kanoronhkwáhtshera'

At the revival of the Mohawk language, people wanted to learn their language and their culture. The more they would learn, the more they would say, “Hey, there’s nothing wrong with who I am, there’s nothing wrong with me. There is nothing wrong with the way Shonkwaia’tíson’, or God, has made me. I am perfect just the way I am.”

Living that dream

I met Onkwehón:we who didn’t even speak English all the way from Manitoba, BC, and other Western provinces. Many came to me and said, “I got no education. I never went to school. But I worked in my community for many years. I know my culture, I know my traditions, I know my history, and I know the church.”

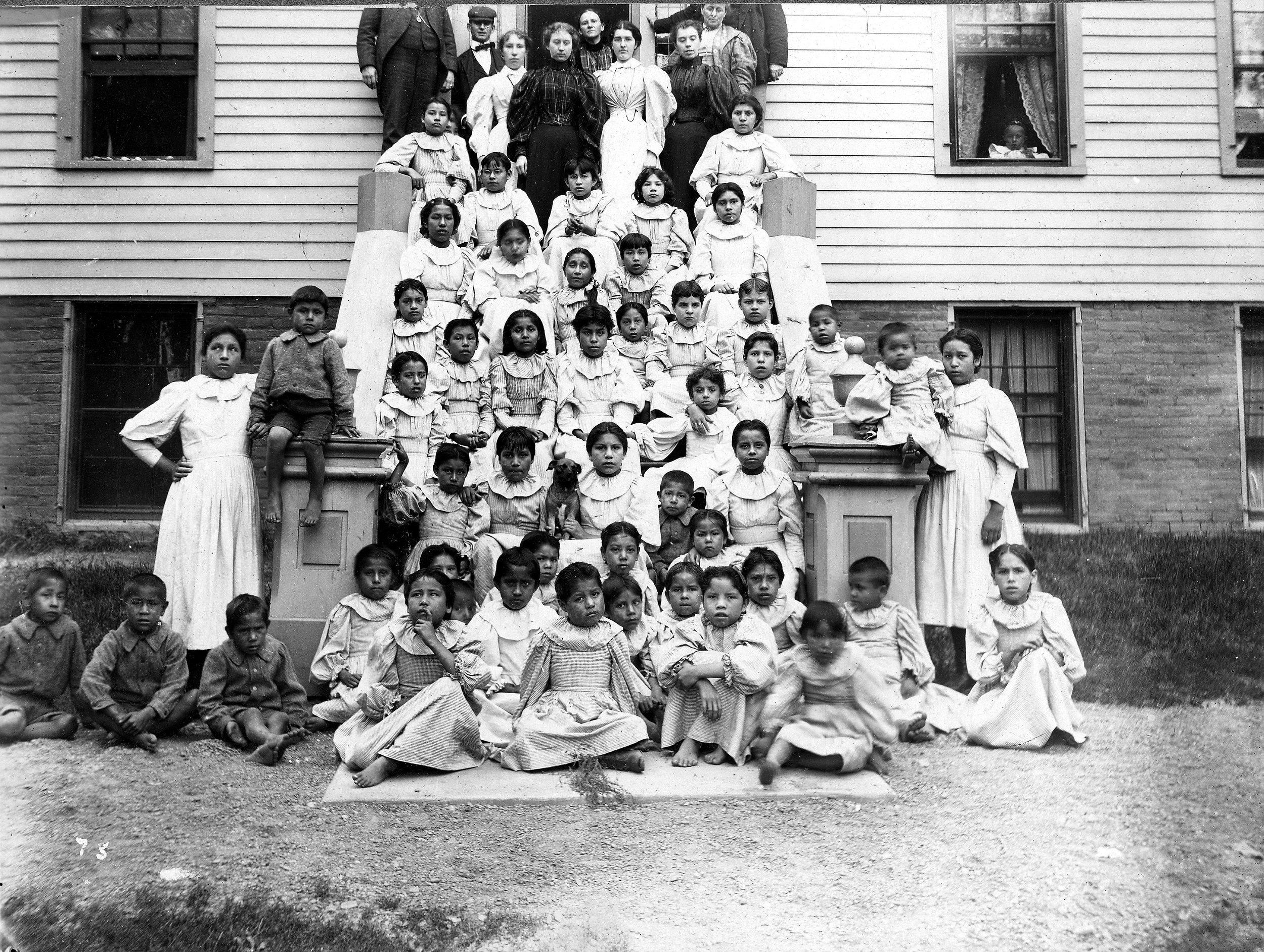

It keeps going on

As a kid, I was so confused with my mom. I never knew what she went through. I couldn’t say anything about it. If I had known the way she grew up, then I would’ve understood better. She didn’t tell us what she went through. All she would do is start crying when she mentioned the school.

Good and proud

I worked at Karonhianónhnha' Tsi Ionterihwaienstáhkhwa' for 20 years, starting in 1989. When I started, they were struggling to find teachers. We had quite a lot of speakers back then but few that would teach. I began as a volunteer teacher’s assistant to help a friend of mine who taught social studies and science because he would sometimes be at a loss for words.

Change is hard

It seems everything important begins with a protest. When Kanien’kéha immersion first started, it became an issue in our community. It was thought that teaching culture and language would hold one back from making progress in school.

Make one school

There was a big sign in front of where the Ed Center used to be, where the library is today, inviting people to come and give their opinion. There were many opportunities for parents to voice their opinion or concerns. People did not come forward, so it looked like it was a go. I remember thinking it will never work. I hear the talk. Parents will not accept this, so I brought that up at an admin meeting.

If you don't use it, you can lose it

I’ve helped write a lot of books. I helped with the typing but it would take so long because the language is not like English. There are only 11 letters in our language but there are so many accents. Language groups in several Mohawk communities have used those books we made.

Black and blue

Ti-bert used to dream out loud in Mi'kmaq, which they called the devil’s language. And if you spoke in Mi'kmaq, or even in English, you got beaten. Every night Ti-bert would miss his grandmother and would dream about her. So of course, he spoke in his sleep in his language because his grandmother didn’t speak French or English.