Proper indian

Welcome sign in Kanien’kéha at Akwesasne Mohawk School. Taken in October 1985. (Credit: George Mully)

Story told by Robert Diabo

I grew up speaking Mohawk, until English came in. My older sisters were learning it in school, so they started to use English in the house.

Little by little, you pick it up and when I went to school, it was every day.

The older people back then couldn’t communicate in English or any other language, strictly Mohawk.

It’s a good thing it’s coming back.

A couple years ago I was at the hospital for an appointment. These two young girls, maybe 10 or 11 years old, came in and sat behind me. They were speaking Indian.

Teacher Louise Diabo teaches “the Lord’s prayer” in Kanien’kéha to children at the Little Cuyler Presbyterian Church in Little Caughnawaga in 1939. (Credit: Irving Kaufman/Brooklyn Daily Eagle)

I was surprised they were speaking so good because this was only from learning it in school.

Usually, you pick up a couple words and put them together. Then you have some words depending on what sentences you use and it changes the whole meaning.

But these two young girls were speaking proper Indian. So it’s nice to see they are teaching proper Indian in school, it’s getting better all the time.

Kanien'kéha version

↓

Kanien'kéha version ↓

Tkarihwaié:ri Tsi Ní:tsi Tiatá:tis Ne Onkwehonwehnéha

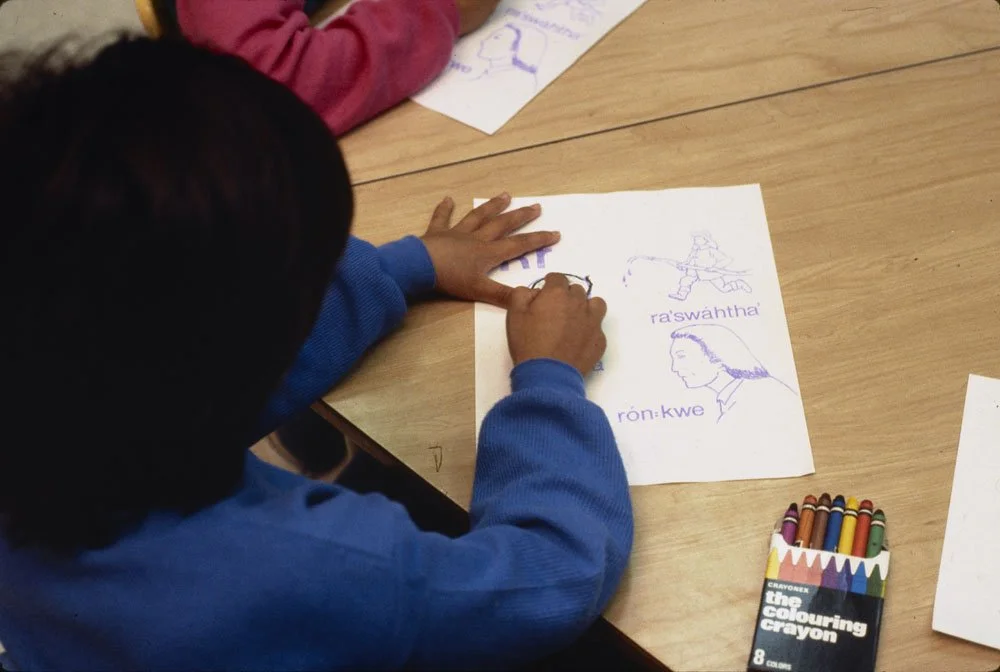

Child working on a Kanien’kéha worksheet at the Akwesasne Mohawk School in November 1985. (Credit: George Mully)

Robert Diabo roká:raton

Kanien’kéha wakahronkha’onhátie’ shiwakatehiahróntie’, tsi niió:re’ Tiohrhèn:sha tontáweia’te’. Tsi ionterihwaienstáhkhwa’ shos kontiweientéhta’s ne khehtsi’okòn:’a’, thò:ne ki’ tontáhsawen' tsi tiakwèn:teron wa’kontá:ti’.

Ken’ nikonhatié:ha, ténhsehkwe’ tánon' thia’tewenhniserá:ke iahontkón:tahkwe’ shontakatáhsawen' tsi katerihwaiénstha’.

Iah ki’ tehatikwénieskwe’ ne thotí:ien's ne eh shikahá:wi Tiohrhèn:sha’ ahontá:ti’ tóka’ ni’ noià:shon na’kawennò:ten’s, nek Kanien’keha kénhne’.

Ioiánere’ se’ tsi ken’ na’tontaiawenonhátie’.

Tohkára niiohserá:ke’ tsi náhe’ tsi tetehshakotisniè:tha’ ié:ke'skwe’ othé:nen wakaterihwahserón:ni. Kí:ken tekeniiáhse tekeniksà:’a, ki’ ónhte’ oié:ri tóka’ ni’ énska iawén:re’ nitiotí:ien's, ákta nontákene’ akhnà:ken wa’tiátien'. Onkwehonwehnéha’ tiatá:tiskwe’.

Onkenehrá:ko’ tsi niioiánere’ tsi ní:tsi tiatá:tiskwe’ ase'kénh nek tsi ionterihwaienstáhkhwa’ nitiawé:non tsi ní:tsi tiatá:tis.

Iotkà:te’, ken’ nikawén:nake ténhsehkwe’ tánon tehsekhánion'. Sok ká:ien' nó:ia’ nikawennò:ten's néne tekontténie's tsi nahò:ten' kontí:ton, nè:’e tkaia’takwe’ní:io kátke énhsatste’ nó:nen enhsatá:ti’.

Nek tsi kí:ken tekeniiáhse kwah tkarihwaié:ri tsi ní:tsi tiatá:tis ne Onkwehonwehnéha. Ioiánere’ ki’ naiakotó:ken’se’ tsi tkarihwaié:ri onkwehonwehnéha tiakotirihonnién:ni ne tsi ionterihwaienstáhkhwa’ nonkwá:ti, kwah tiótkon taioianerèn:sere'k.

Edited by: Aaron McComber, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Translated by Karonhí:io Delaronde