The Indian Act

The Indian Act is a structure created by the Canadian government that governs the rights and status of the Indigenous population. The act also creates a set of obligations that the government owes to First Nations people.

Established in 1876, the Indian Act was originally created to control and assimilate Indigenous people and their culture. It acted as a colonial guide to help incorporate the European way of life into the territory.

The act was used as a tool by the Canadian government to restrict First Nations people from practicing their traditions and culture. Band councils replaced traditional ways of governance, and if a person with recognized Indian status chose to receive a higher education or vote in Canada’s government elections, their status would be revoked. This procedure of status removal was commonly referred to as enfranchisement.

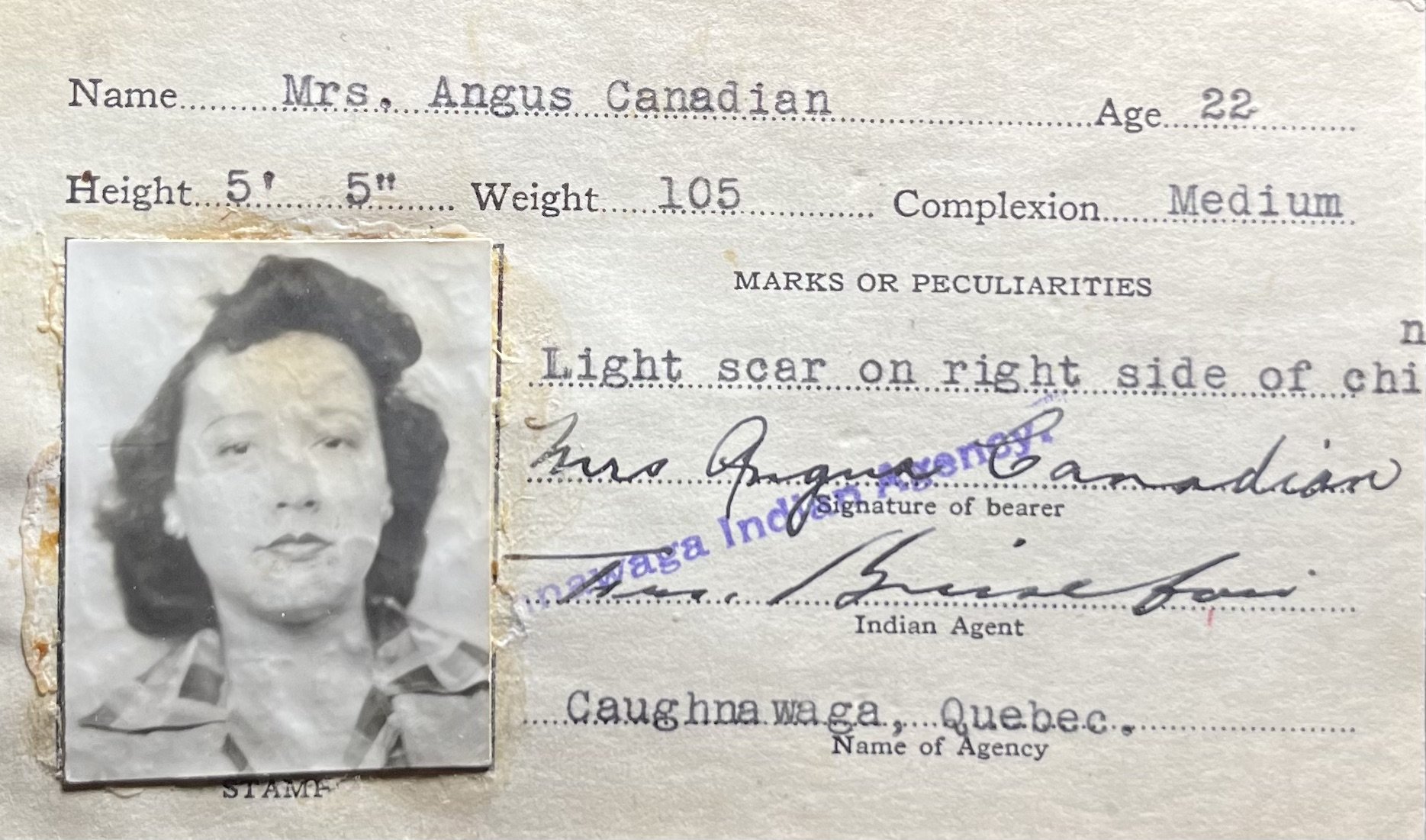

To be considered a “status Indian” meant to be legally recognized under the Indian Act. In 1876, this meant being an Indigenous man that was part of a band; or being his wife or child. To have Indian status means to have federally recognized benefits and restrictions put in place by the Indian Act. The requirements to have status have since shifted to be more encompassing of a larger population however, women’s rights in the Indian Act were historically very limiting and restrictive.

A woman with Indigenous blood had no right to participate in any band council or government activities. Furthermore, if a women married out of the bounds of her reserve, her Indian status would be invalidated immediately. Meanwhile, men who married a non-Indigenous spouse were able to keep their status and their new wife would be granted Indian status.

In 1951, the Canadian government passed the “double mother” law which stated that an Indigenous child would lose their status on their 21st birthday if both their mother and grandmother didn’t meet the qualifications to obtain Indian status. This caused irreversible harm to First Nations women and children, as they lost their identity and inherent rights.

The Indian Act prohibited the act of requesting or receiving any type of monetary funds. This was put in place in hopes that Indigenous people wouldn’t try to use money towards pursuing land. They were furthermore prohibited from receiving legal council or hiring lawyers. Alcohol was banned from reserves and those who wished to consume any had to give up their Indian status. To worsen these restrictive conditions, the government also authorized the “pass system” - a structure that limited Indigenous people from leaving the reserve, unless it was for the case of children being taken out and sent to residential schools to further push colonial practices on them.

To ensure that people were respecting the laws, Indian agents were created to monitor the reserves. In effect from the 1830s to 1960s, Indian agents acted as Canada’s representatives. Their day-to-day tasks included enforcing the rules of the Indian Act, managing reserves, distributing rations of money, food, and medicine, and acting as an intermediary during disputes between the First Nations and the Canadian government.

Indian agents were typically previously farmers or priests, who were sent far from their homes to live on desolate reserves and territories. Upon taking on the job, they received up to $1200 a year which is equivalent to $27,000 in today’s economy. This compensation was above the average salary, therefore making it a high-paying and treasured job.

Of course, the majority of agents were white men who passionately believed in and practiced the Catholic religion. Although some were sympathetic towards First Nations people, many felt no remorse towards the consequences they inflicted on the Indigenous population and believed that assimilation was necessary. A few agents spoke out against the government's harsh laws, such as banning powwows and potlatch dancing. However, they typically lost their jobs for doing so, which led to agents rarely challenging the Indian Act.

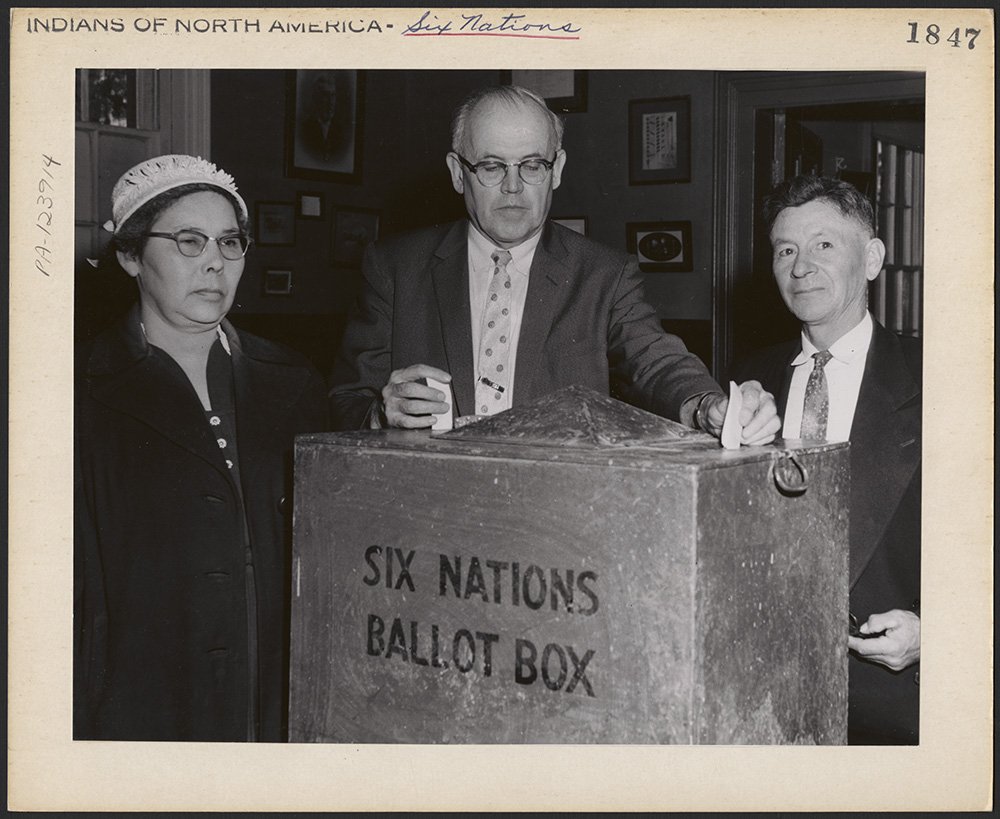

Beginning in 1958, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker began working on the Canadian Bill of Rights, which worked towards the equality of all Canadian citizens. At this time, Indigenous people saw the opportunity to advocate for their right to vote since they were considered to be living in Canada.

On March 31, 1960, the Canada Elections Act voted in favour of Status Indians right to vote without losing their status. In the year following, the enfranchisement legislations created by the government were abolished.

Throughout this time, Indigenous women were still minorities in society and began speaking up for their rights. Mary Two-Axe Earley, a notable activist, created campaigns to show the abuse inflicted upon First Nations women. Other women, such as Jeanette Corbiere Lavell, took the Canadian government to court after her Indian status was terminated due to marrying a man from Toronto.

In 1973, Jeanette’s case was reviewed by the Supreme Court of Canada in which the court believed that she had not been deprived of any rights or equality since she was still equal to all other women in the country.

In another case pertaining to Wolastoqiyik woman, Sandra Lovelace Nicholas was banned from her community after losing her status for marrying a white man. Both Sandra and Jeanette’s cases caught the attention of the United Nations. The UN agreed that Canada breached Article 27 of the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

In 1985, Canada’s treatment towards Indigenous people became a significant concern for surrounding countries. To respond to this external pressure, Canada passed Bill C-31 which permanently ended all enfranchisement and prejudicial laws against their First Nations citizens. Furthermore, this meant that women and children who were stripped of their identity were given their status back.

Even if the more discriminatory laws were erased, the impacts are still felt today. The Indian Act continues to serve as a framework for the relationship between Indigenous people and the Canadian government, as well as clarifying the status and rights of First Nations.

Although it feels like the Indian Act and agent’s strict rules were banned a long time ago, they have left long lasting impacts on the Indigenous society. The act is still in place today, with systems such as the band council still in effect. Loss of language and traditions, land restrictions, and assimilation, are just some examples of what still affects Indigenous communities today. Despite all this upheaval and loss, there is constant work towards one day living in a society free of the Indian Act’s control.

SOURCES AND FURTHER RESEARCH

ARTICLE: Indian Act (2006) by Zach Parrott (The Canadian Encyclopedia)

ARTICLE: Indian Agents in Canada (2018) by Robert Irwin (The Canadian Encyclopedia)

BOOK: 21 Things You May Not Know About The Indian Act (2018) by Bob Joseph

ARTICLE: The pass system: another dark secret in Canadian history (2015) by CBC Radio