Little Caughnawaga & Ironwork

From left to right, ironworkers Allan Delaronde (Kahnawake), Doc Alfred (Kahnawake) and Art Oakes (Akwesasne) stand on the 110th floor of the North Tower of the World Trade Center in New York City. Taken circa 1970. (Courtesy: Kanien'keháka Onkwawén:na Raotitióhkwa Language and Cultural Center)

Little Caughnawaga, in Brooklyn, New York, was known as a home away from home for many Haudenosaunee people seeking out a new life for themselves. The community of Little Caughnawaga was known to house up to roughly 800 Haudenosaunee people for 40 years from the 1920s to the 1960s.

Dating back to the 19th century, the Canadian Pacific Railroad hired men from Kahnawake to help build railroads across the reserve. As well, many fearless Mohawk men took on the job of building the Victoria bridge across the St. Lawrence River. They were known to have a real expertise in climbing and working at extreme heights, with people referring to them as having "nerves of steel.”

In 1907, several men from Caughnawaga - the anglicized word for Kahnawake - were helping build the Quebec bridge that connected Sainte-Foy and Levis. On August 29th of 1907, an engineering flaw led to the collapse of the bridge, killing 75 of the 86 men on the job. 33 of them were from Caughnawaga, leaving many families without fathers, husbands, and sons. This event is remembered as the Quebec Bridge Disaster and is commemorated in Kahnawake by two steel beam crosses at the east and west end of the reserve. In order to ensure that they wouldn’t encounter another devastating situation like this again, the community decided that there should never be so many men from Kahnawake working on the same jobs.

Men, largely from Kahnawake and Akwesasne, began to migrate to where work was needed. They could be found working all over Turtle Island from Ontario to Chicago, even going as far as San Francisco, but New York City had the largest demand for those “nerves of steel.”

Manhattan was in a building boom, with a demand for construction of bridges and buildings such as the George Washington bridge, the Madison Square Garden, and the United Nations building. With such a request for work, job sites had to be divided into 3 gangs: the raising gangs, fitting-up gangs, and riveting gangs. As the beams, steel columns, and girders arrived at the construction site, the raising gang used the cranes to set the steel pieces in place. The fitting-up gang would make sure the pieces fit properly and would tighten them with the bolts. Finally, the riveting gang would heat up the rivet pins and pass them to each other, to then form and align the structures together.

The riveting gang usually required ironworkers to work in teams of four. The Kanien’kehá:ka were known to excel at riveting and would typically choose to work in a team with fellow members of their nation or community to ensure there was trust between one another.

Ironworkers from Kahnawake typically left their families for months at a time, depending on the work contract they were given. Men from Kahnawake were usually associated with the local unions 361 and 41 when working jobs involving ironwork in New York. With the borough of Manhattan being outrageously expensive to live in, most workers settled just south of the city, in Brooklyn.

During their stays, most men lived in rooming houses with one another before heading back to Canada at the end of a job. This routine changed in 1927 when ironworker Paul Diabo, was arrested on a job in Philadelphia for being considered an “illegal alien.” His defence team argued against the U.S. government, stating that all rights and privileges lost during the war of 1812 should be given back to those of Indigenous heritage according to the Jay Treaty of 1794. Since the courts viewed the Treaty and saw that the Mohawk nation was independent from the United States and Canada, all ironworkers were then granted access to travel and work freely between the two countries.

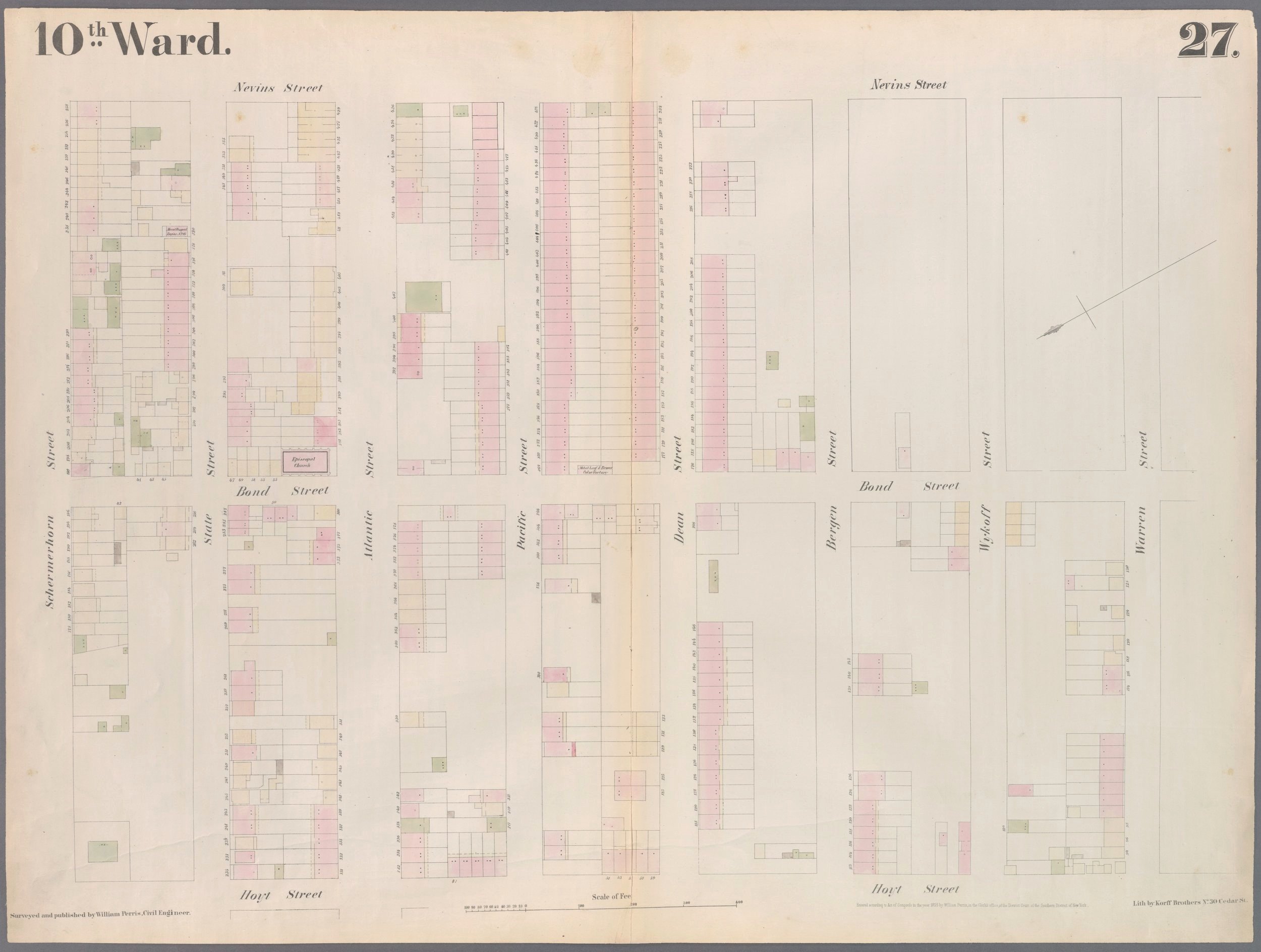

Family dynamics weren’t the same for those who had their husbands working far from home for such long periods of time. Therefore, many women packed up their children and began seeking a new life for their families in Brooklyn. Specifically, they settled in the Boerum Hill neighbourhood, on streets like Nevins, Bond, Atlantic, Pacific and State.

While men were building sky-high buildings, the women could be found doing odd jobs from working in factories to housekeeping. Some women opened up boarding houses in Little Caughnawaga to not only generate some income for themselves, but to help those who came from Kahnawake for work and couldn’t afford to live on their own.

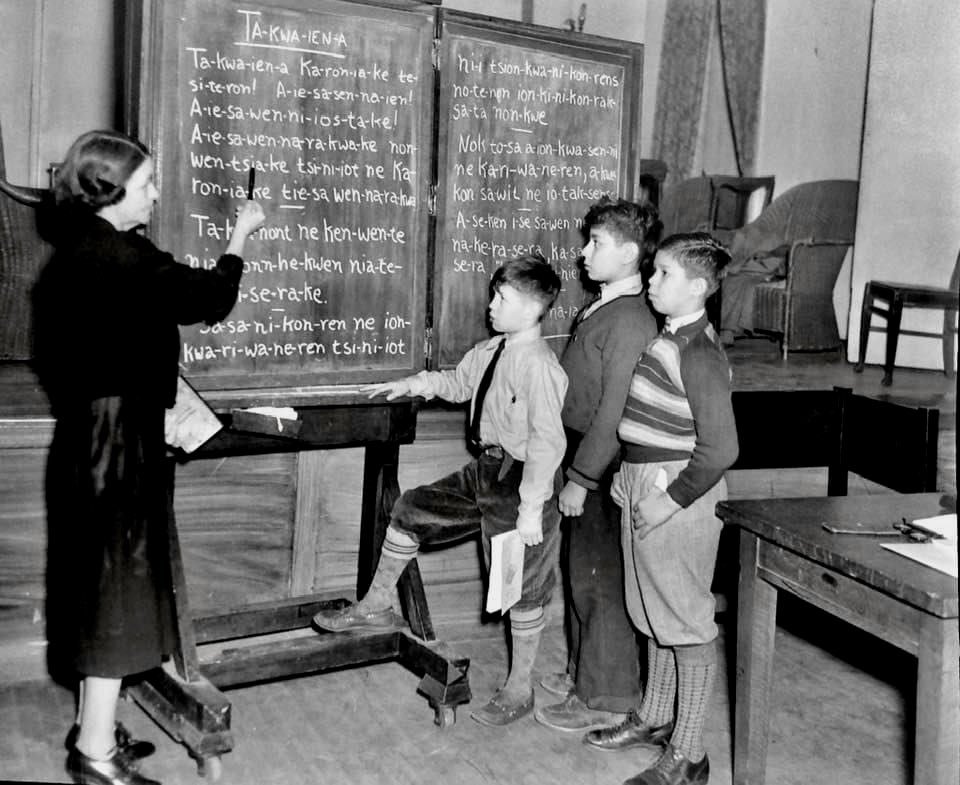

The citizens of Brooklyn began to notice the growing population of Mohawks and started tending to their cultural needs. Corner stores stocked up on ingredients for corn bread and corn soup, and the local Reverand David Munroe Cory learned to speak Kanien’kéha for those who attended his weekly services at the local religious movement which was formerly known as the Cuyler Presbyterian Church. There were a couple bars that opened as well, such as the Wigwam bar and Spar bar, where many men would go have a drink after their tiring shift of erecting steel forms all day.

Although many people have great memories in Little Caughnawaga, there were also times of disparity. When one job ended, there was usually a 2-3 month wait until another came along. Many families were left struggling financially during that time, not being able to feed themselves. But as soon as another job site needed men, the income would become steady again. Many people usually called this "feast to famine”, or vise-versa.

When summer came around, families would often carpool with one another back to Kahnawake. With what is roughly a 6-hour drive from Kahnawake to Brooklyn today, was typically 12-18 hours back then because of the lack of road infrastructure and connections. When people came home for the summer, many of their relatives were happy to see them, but there was also intolerance from locals who would refer to them as “Brooklyn bums.” Families would spend the whole summer season in Kahnawake before making the long trek back to Little Caughnawaga in the fall.

The boom of Little Caughnawaga ended in the 1960s with many families deciding they were ready to come home or expand their horizons to other places of work. The expansion of highway 87 made travel time much shorter so many ironworkers decided to do their duties during their 5-day work week and come home to their families on the weekend.

Although Little Caughnawaga is now just a historical memory, the legacy it has left behind still goes on today. Some of the most notable structures built by these courageous men include the Empire State building, the Chrysler building, the Rockefeller Plaza, as well as both the old and new World Trade Centers. Many Mohawk ironworkers dedicated time to helping clean up the rubble from the 9/11 attacks in New York City. What started out as a way of making a living, has now become a rite of passage for many Kahnawake locals as they can still be seen today creating the backbone of countless different structures from skyscrapers to bridges.

Sources and further research

FILM: Little Caughnawaga: To Brooklyn and Back (2008) by Reaghan Tarbell

ARTICLE: Little Caughnawaga by Isabel Lockhart

PODCAST AND ARTICLE: Unmapped: NYC (2024) by Unreserved CBC

ARTICLE: Quebec Bridge Disaster (2013) by James H. Marsh

ARTICLE: The Mohawks Who Built Manhattan by White Wolf Pack

ARTICLE: Brooklyn Mohawks (2009)